A glimpse of what a future bus operation might look like can be seen at the depot of Regionalverkehr Köln GmbH (RVK) in Wermelskirchen – one of currently two locations of the transport company where buses are refueled with hydrogen: trailers deliver the environmentally friendly fuel, which is initially stored in low-pressure tanks at 5 to 50 bar. Their volume of 230 m³ provides 1 t of hydrogen, allowing the RVK bus fleet to operate for two days. Two high-pressure compressors housed in two 20-foot ISO containers – one for daily supply, the second with the same capacity as redundancy – compress the hydrogen to 420 bar. It is then stored in nine cylindrical tanks.

The dispenser on the premises is cooled to –5 °C to achieve refueling times of under ten minutes. Compared to fully electric buses, the short refueling time is one of the advantages of H2 technology. Another is the minimum range, which for RVK buses is 350 km year-round. This meets the operational parameters of the diesel buses that still dominate the German bus industry. The RVK fleet, currently comprising 359 units, is set to include 160 fuel cell buses from manufacturers Solaris, Van Hool and Wrightbus within a year. They serve suburban intercity routes in the greater Cologne area, where currently available fully electric buses could only operate with time-consuming intermediate charging.

Germany leads Europe in hydrogen buses So, all is well, and H2 technology is the future of the bus industry in Germany and Europe? One might think so. However, the reality is more nuanced. In most countries on the continent, the deployment of hydrogen buses is stagnating. In the Netherlands, one of the pioneers in bus electrification, fuel cell models accounted for 20% of new city buses in 2021. In the following two years, the share dropped to 13% and 5%, respectively, and finally to 0% by the end of 2024. According to the 2024 Annual Report by European Bus Data, 378 hydrogen buses were sold in Europe last year (2023: 207, 2022: 99). Compared to 7,843 battery-electric, 3,379 hybrid and 2,805 CNG buses, this figure represents only a vanishingly small share. In 2024, Germany achieved a market share of 13.34% for new registrations, measured against all city buses with alternative drives to diesel. Otherwise, hydrogen buses are currently sold in significant numbers only in Spain, Italy, Poland and the United Kingdom – with very low single-digit market shares.

The reason for this lies less in the fuel cell technology, which generally functions quite reliably. Instead, it is financial considerations that deter transport operators from making purchases. H2 bus models themselves are only slightly more expensive than their fully electric counterparts. Unlike the latter, they typically require only a relatively small buffer battery, which largely offsets the significant additional cost of the fuel cell. An exception is the Mercedes-Benz eCitaro G fuel cell with the new “H2 mode”, in which the large 392-kWh battery is supplemented by a 60-kW hydrogen-based range extender that always operates in the efficient range between 20 and a maximum of 40 kW. This means hydrogen is only consumed when required to meet range demands.

Efficient H2 buses The background is clear: the use of green hydrogen – the only ecologically sensible option – is currently very expensive. At filling stations, its price is currently between €13.85 and around €14.50/kg – and this despite being highly unprofitable for suppliers and tax-exempt. If tax components similar to those for diesel (40%) or electricity (29%) were added, significantly higher prices would apply.

For comparison: the 50 H2 trucks from Hyundai in Switzerland operate at CHF 22/kg, which currently equates to around €0.72/kWh. At the same time, commercial electricity in Germany is available at an average net price of €0.21/kWh. Some transport operators – especially those with annual consumption exceeding 100,000 kWh – are now entering the electricity procurement market themselves with the help of their electricity provider or specialized brokers. At the Leipzig electricity exchange or in OTC forward trading (OTC = over-the-counter), they can purchase electricity years in advance, providing planning security. On the forward market, the price per kilowatt hour for delivery years 2025 to 2028 is currently only €0.075 to €0.09. Taxes, grid fees, levies and surcharges are added. Nevertheless, energy costs of around €0.15 to €0.17/kWh can be achieved.

Although many H2 bus models are now quite efficient in terms of consumption – in a test, we operated the Arthur H2 Bus 12 M at between 4.8 and 7.2 kg/100 km depending on topography, with an average of around 6 kg/100 km for this 12-meter standard bus – hydrogen-based vehicles still cannot compete with fully electric counterparts in terms of cost structure.

An example calculation: 6 kg of hydrogen costs €83 in the best case. The fully electric 12-meter solo bus consumes an annual average of around 120 kWh/100 km. This results in energy costs of €25/100 km. This is also cheaper than a diesel city bus, which consumes an average of 42 l/100 km. Diesel costs €1.24/l net (as of March 2025) on the wholesale market, totaling €52/100 km.

If electricity for e-buses is sourced from the Leipzig electricity exchange, energy supply costs for the vehicles drop to around €18 to €20.50/100 km at €0.15 to €0.17/kWh. The fuel cell bus thus generates at least three times the energy costs of its fully electric counterpart, and in the worst case even more than four times as much.

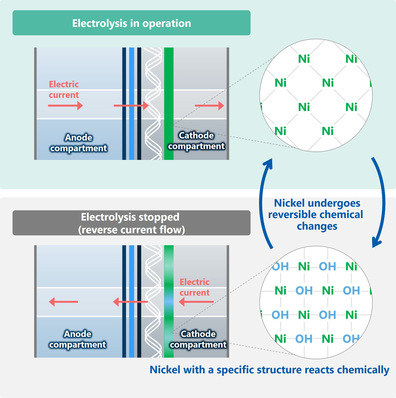

RVK, for example, is currently considering entering its own hydrogen production using a large-scale megawatt-class electrolyzer. This would reduce the cost of green fuel. The model could be suitable for many municipal transport companies that are part of a municipal utility. After all, municipal utilities are almost always energy producers themselves, which reduces electricity costs in the electrolysis process.

Wiesbaden-based ESWE, one of the pioneers in hydrogen for public transport, on the other hand, ended its involvement with fuel cell buses in spring 2023. The company handed over its in-house filling station, which had been in operation since 2020 and subsidized with €1.9 million as part of the Mainz Wiesbaden Transport Association (VMW), to its partner Mainzer Verkehrsgesellschaft (MVG). MVG also took over five of the ten H2.City Gold buses from CaetanoBus that had been decommissioned by the Wiesbaden partner. The reason was drastic cuts in the city budget, with ESWE Verkehr required to save €17 million. As a result, the Wiesbaden City Council decided that the transport company had to withdraw from “non-essential projects” – including a hydrogen bus fleet and filling station.

© Claus Bünnagel

H2 refueling network must expand Another handicap for hydrogen technology in the bus industry is the refueling infrastructure. It is still sparse and is currently hardly expanding – on the contrary. In Austria, oil company OMV has just dismantled its entire public H2 refueling network due to lack of profitability. German market leader H2 Mobility is currently closing a number of smaller, unprofitable sites, mainly with 700-bar technology. Eleven were closed by the end of Q1 2025, with another eleven to follow by the end of Q2.

The company is instead focusing on regional hydrogen hubs in areas with high demand, such as metropolitan regions or along major transport corridors. In the next six months, two new sites with 350-, 500- and 700-bar refueling options will open in Düsseldorf and Ludwigshafen. In 2024, large stations already opened in the Rhine-Neckar focus region in Heidelberg, Mannheim and Frankenthal.

There are technical changes: the new generation of refueling stations features more dispensers, larger hydrogen volumes supplied via trailer systems, and significantly more powerful technology. This transformation is justified by the dampened market ramp-up for passenger cars and small commercial vehicles. In contrast, the share of 350-bar refueling for buses and trucks is increasing – slightly, but steadily. In March 2025, H2 Mobility recorded for the first time a higher sales share for 350 bar than for 700 bar. With a share well above 50%, this figure could mark a turning point. At the same time, total hydrogen sales rose by a moderate 10% compared to the same month the previous year. By the end of the year, the majority of revenue is expected to be generated by 350-bar demand.

However, truck and bus manufacturers such as Daimler Truck are also relying on 700-bar technology for commercial vehicles or even liquid hydrogen. Corresponding vehicle models are expected to come to market within the next three years. What refueling options will be available for the latter variant, with temperature levels below –253 °C, remains completely open.

Subsidies urgently needed In this difficult situation, there is currently little support from policymakers for vehicle manufacturers, transport operators and refueling station operators. Following the subsidy freeze for electrified vehicles in Germany at the end of 2023 – which of course also affects fully electric models – the economic gap between fuel cell and diesel buses has continued to widen, despite some state-level subsidies. Transport operators are therefore holding back on procurement, ordering only within the framework of subsidized state, federal or EU projects, if at all.

When it comes to financing, much will depend on the measures taken by the next federal government to get the stalled transport transition moving again. In addition to vehicle subsidies, it must also boost the production of green hydrogen. This requires large-scale electrolyzers, ideally coupled with photovoltaic and wind farms, to convert surplus electricity into hydrogen cost-effectively and, if possible, around the clock. Only in this way can the cost of the environmentally friendly fuel be reduced. Experts agree that hydrogen can only be used economically in road transport when prices per kilogram fall – preferably significantly – below €6.

Solutions should therefore be implemented quickly, especially since promising areas of application are already within reach. In long-distance transport with trucks and coaches, hydrogen technology could be used efficiently. The first H2 coach models, such as those from Basque manufacturer Irizar or Chinese company Wisdom Motor, have already been presented. And for the intercity segment with high daily circulation scenarios, fuel cell buses would be particularly well suited.

© Claus Bünnagel