The diesel engine is the benchmark. That much was clear when Cellcentric set out in 2020 to develop a fuel cell power unit for long-haul heavy-duty transport. That, the company had determined, is the sweet spot for fuel cells. Last-mile deliveries in urban areas can be handled well by battery electric vehicles. For heavier vehicles covering a few hundred kilometres – refuse collection, for example – hydrogen combustion engines score with their comparatively low acquisition costs. It is only on long-haul routes, where the kilometres are limited only by drivers’ mandatory rest breaks, that fuel cells really come into their own. That is because fuel costs become more significant relative to the initial investment, explains Joachim Ladra, Head of Sales, Marketing and Communications, outlining the strategy.

Today, more than 500 people at Cellcentric are working on this single product: a fuel cell power unit designed to replace a diesel engine. The unit is intended to fit precisely into the installation space occupied by a 13-litre, six-cylinder diesel engine. It should deliver comparable performance and achieve similar range. And with the next generation, which Cellcentric plans to present at Hannover Messe 2026, that goal could be within reach.

The road to this point has been long, and strictly speaking began in the 1990s. Standing in the pilot production hall in Esslingen is the first fuel cell vehicle ever to take to public roads – the Necar1 from Mercedes-Benz. The entire cargo area of the van is filled with tanks, pipes and valves, and yet it trundled along the motorways at a top speed of 80 km/h with its 30 kW output.

© Cellcentric

From Necar1 to next generation

Today’s state of the art is many miles removed from those beginnings. For several years now, it has been possible to have a truck converted to fuel cell drive by commercial specialists. But this is a highly bespoke undertaking, with specialists having to find the best location in the vehicle for each component. On buses, the tank usually goes on the roof; on trucks, behind the cab. Competitor Hyundai introduced the first series-production hydrogen trucks in 2020. The latest variant from 2025 achieves ranges of over 700 km. However, the fuel cell power unit delivers 180 kW – considerably less than the 350 kW electric motor installed. Full motor power can therefore only be called upon if the fuel cell has charged a buffer battery in advance.

Cellcentric, too, has most recently been producing fuel cell units with an output of 150 kW. Two of these units in Daimler Truck vehicles have demonstrated publicly that, with predictive battery management, this output is enough to cross the Alps.

But the new generation is set to make the leap to up to 375 kW – in the same installation space, of course. Cellcentric put this figure on record in a paper at the Vienna Motor Symposium – and will be held to it in April. The fuel cell should then be able to supply the electric motor continuously at full power.

The second improvement lies in efficiency – or, put another way, in fuel consumption. This is set to fall by 20 percent compared with the predecessor model. “At hydrogen prices below €8, the total cost of ownership also becomes attractive,” says Ladra.

The third critical point is cooling. If the cells overheat for extended periods, they degrade. Cooling is not technically difficult, but it requires space and costs money. The hydrogen trucks from Daimler Truck fitted with the previous fuel cell generation therefore have an extended tractor unit to accommodate the cooling system. Since overall length is limited by regulations, this comes at the expense of cargo capacity. The new generation has a 40 percent lower cooling load, the company says, partly because it tolerates significantly higher temperatures. This allows the cooling system to fit within the vehicle’s standard installation space.

A key factor behind several of these improvements is that Cellcentric is now using a single fuel cell system with larger cells. The three stacks it contains operate at a higher voltage, which at the same power output means lower current and thus fewer losses in the form of heat. The catalyst composition has also been refined.

© Cellcentric

Factory undergoing conversion

Cellcentric is now transferring all these improvements to the pilot production facility in Esslingen, which is currently in the midst of conversion. Some stations are already complete; others are still under construction. At the start of the production line stands the “big kitchen mixer,” as Ladra jokingly calls the metal tank. It holds 100 litres. This is where Cellcentric mixes its ink for the cathode and anode coatings. It contains platinum, iridium and solvents. Beyond that, Ladra reveals little. “That’s our Coca-Cola recipe. Only a handful of people know it. It’s so secret that we haven’t even filed a patent for it,” he says.

What is no secret is that the tank containing this magic potion is transported to the next station in the pilot facility by an ordinary forklift. “We’re developing the individual production steps here, not the transport. We’ll deal with that when we later set up series production for larger volumes.”

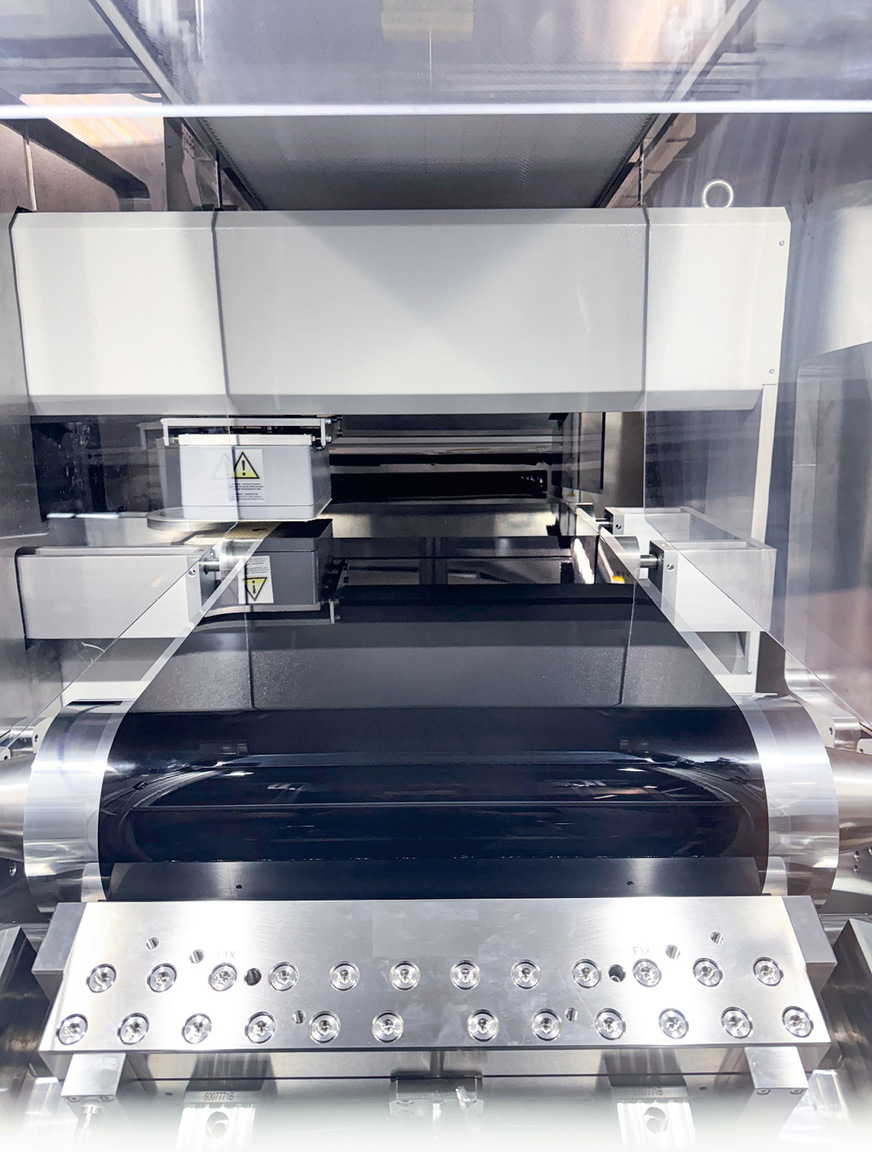

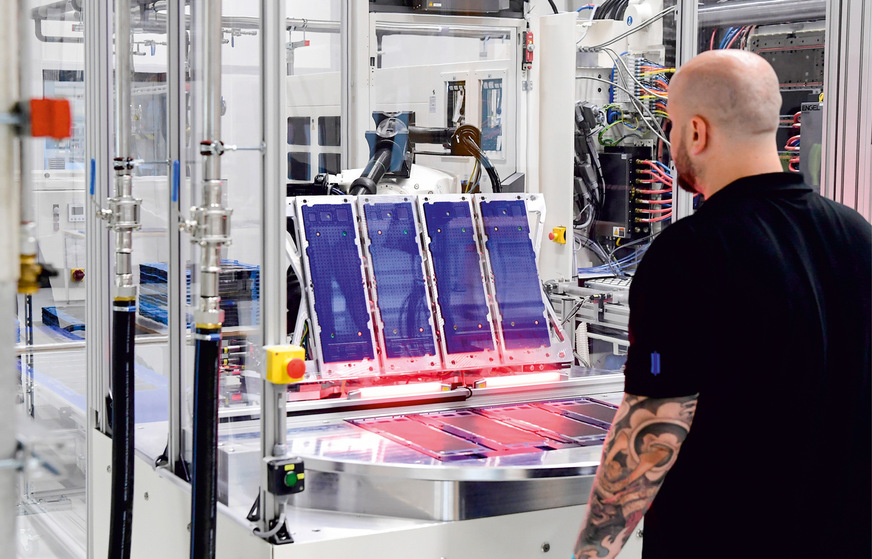

The development work can be observed at the next station. There, the ink is applied to long foil webs in a roll-to-roll process to produce anodes and cathodes. The webs run over several guide rollers. Before the valuable ink comes into contact with them, they are cleaned, dried and carefully inspected. From the coating unit, the web passes seamlessly into the drying oven – one of the largest machines in the hall. After the oven, the web with its electrode layers winds back onto a roll.

Ultimately, all inspections will of course be carried out inline and automatically. Today, two men with measuring instruments and laptops are stationed here. They are in the process of commissioning the system following its conversion for the new generation. In recent weeks, they have invested considerable time and effort to get all the parameters right. Now, at last, everything is working. Apart from safety glasses and safety shoes, they wear no special clothing, as there are no cleanrooms in the factory. Each section of the equipment is enclosed and set to the required cleanliness level – in its own mini-cleanroom, so to speak.

Sandwich from the roll

In the subsequent production steps, where the layers are assembled, Cellcentric also works with rolls. First, the anode and cathode webs are brought together; then the delicate and comparatively expensive membrane is inserted between them. The result is a catalyst coated membrane, or CCM.

At the next station, this membrane sandwich is first supplemented with three more layers. To distribute the reaction gases evenly, a gas diffusion layer (GDL) made of a conductive carbon material is still needed on each side. And to give the unit stability, frames are required. These also come from a roll. Only when all layers are neatly aligned is the sandwich cut, positioned, bonded and singulated. The framed membrane electrode assembly is now complete (membrane electrode frame assembly, MEFA). At a further station, this is sealed by injection moulding to become a sealed membrane electrode frame assembly, or SMEFA.

Now the bipolar plate is still missing. This is one of the few parts that Cellcentric does not manufacture itself. “We use graphite bipolar plates. Metal would be easier to handle, but tends to undergo chemical reactions at high temperatures. That means we would have to be more cautious in operation and could only use the cell’s maximum power briefly, for example,” Ladra explains. With graphite bipolar plates, by contrast, the stated maximum power of the fuel cell modules is identical to the continuous power. The individual cell is now complete.

© Cellcentric

Stack with bolted connections

Next comes stacking. To connect the cells into a stack, Cellcentric relies exclusively on bolted connections. This is not the cheapest solution, but it offers the assurance that any cell can be replaced in the event of a defect. Since the entire stack is worth roughly as much as an upper mid-range car, this safeguard pays off. The stack becomes sealed during the subsequent compression – and visibly shrinks at the same time. The heart of the power unit is now complete.

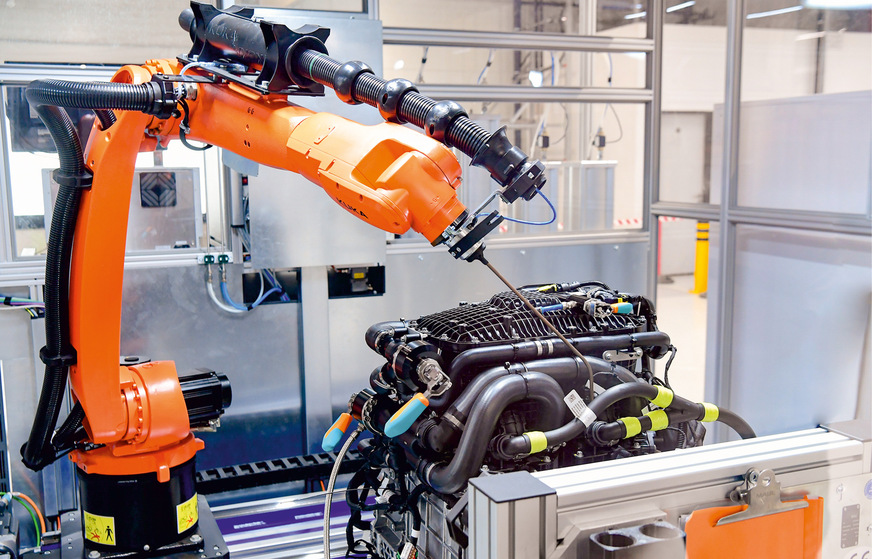

At a final station, everything needed for the fuel cell to function is assembled – from sensors and the coolant pump to the compressor and the DC/DC converter. In the pilot factory, this is largely done by hand by a single person.

Before leaving the factory, the finished power unit must pass three tests. First comes the leak test. A sniffer robot moves its trunk-like sensor unit over all the points where hydrogen might escape. Next, the unit must prove in a high-voltage test that voltage and current are correct. In the end-of-line test, it then has to run through simulated driving cycles for three and a half hours – so it has already practised for the Alpine crossing before it even goes into a vehicle.