In order to turn iron ore into iron, the oxygen must be removed from the ore – a process known in chemistry as the reduction of iron. The classic method for this is the blast furnace. Pure carbon removes the oxygen from the ore, producing iron and CO2. The alternative is so-called direct reduction in a shaft furnace, as operated by Arcelor Mittal for many years in Hamburg, Germany using natural gas. In several steps, hydrogen and carbon monoxide are first produced from the natural gas, and then these gases remove the oxygen from the ore. Since natural gas contains carbon, CO2 is also produced during direct reduction with natural gas – although significantly less than in the blast furnace process. If green hydrogen were used instead of natural gas, CO2 emissions could be reduced even further.

While Arcelor in Hamburg, Germany, decided after much back and forth against iron production with green hydrogen, the company Stegra is currently building such a plant on an industrial scale in northern Sweden. So far, the shaft furnace process has only been used for iron-rich ores. For ore with lower iron contents, direct reduction in a circulating fluidized bed is considered an economically attractive alternative.

Many ores contain too little iron for shaft furnace processes.

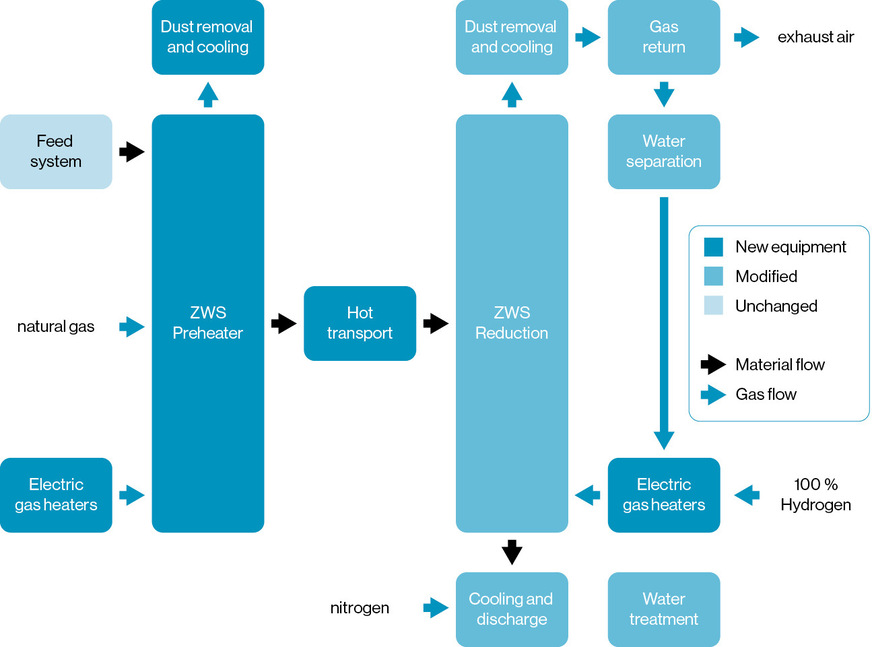

Metso, a Finnish manufacturer of metal processing technologies, inaugurated a so-called Circored pilot plant in Frankfurt am Main, Germany in September. The pilot plant for iron production is based on a circulating fluidized bed (CFB). Compared to the shaft furnace process, the CFB process offers an important advantage. It can also process iron ores with an iron content of less than 60 percent, which, according to Sebastian Lang, head of research and development in Metso’s “Ferrous and Heat Transfer” division, is not common in the shaft furnace process. About 95 percent of the world's iron ore deposits contain only lower iron fractions, so the CFB technology could be a key to decarbonizing the steel industry, according to Metso.

In addition, the CFB process is said to be able to process fine ore directly, which arises in mining after ore preparation. Pelletizing, as is common in traditional steel production, is not required. On the contrary, particle sizes of less than 2 millimeters are well suited for fluidization in a gas medium. In the fluidized bed process, nozzles ensure that the fine material is kept in a turbulent flow and circulates through the reactor. It is a continuous process in which fresh material is constantly fed in and reduced iron ore is removed. The residence time determines the degree of reduction. About 30 minutes are sufficient.

Process requires heat supply.

In contrast to ore reduction with CO, direct reduction with hydrogen is an endothermic process. Therefore, a large amount of heat energy must be supplied. In Metso's CFB process, the fine ore is first preheated to about 900 degrees Celsius. In this CFB reactor, combustion in addition to electric gas heaters introduces extra heat into the process. This also leads to oxidation of the iron ore. This is necessary, for example, with the ore magnetite. “Magnetite is not very reactive,” says Lang. “The dense mineral structure means that hydrogen cannot penetrate well.” Therefore, preheating converts the ore into the fully oxidized and more reactive form of hematite.

Pilot plant receives no hydrogen. In the pilot plant, natural gas and not hydrogen is used for preheating. This is not due to process technology but to availability at the Frankfurt location in Germany. Because there are difficulties in obtaining sufficient hydrogen, Metso is focusing on the core process in the reduction reactor. In this step, reduction of the preheated material takes place in the circulating fluidized bed at about 650 degrees Celsius. The pig iron produced in this process has a metallization degree of about 80 percent. The shaft furnace achieves 95 percent.

© Metso

Further processing into steel in the smelter.

Therefore, further reduction must take place during the processing of iron into steel. This is not possible in the electric arc furnace, the melter. In addition, current electric arc furnace technology is not able to separate the large amounts of slag that occur with ores of low iron content. However, a new technology is currently being introduced. A so-called smelter can further reduce the pig iron, separate the impurities present via the slag, and enrich it with carbon. SMS Group from Mönchengladbach, Germany, a manufacturer of lines for metal processing, is currently building such a smelter in Duisburg, Germany, for Thyssenkrupp to process directly reduced pig iron from the shaft furnace. Metso also has smelter technology in its portfolio. For the first quarter of 2026, it is planned that SMS Group will take over Metso’s metals division and combine the development work on technologies for green steel under one roof.

Pilot plant is intended to convince customers.

Metso developed the CFB technology in the 1970s and has long used it for various material processing applications. For iron production, the company already built a demonstration plant in Trinidad at the end of the 1990s with a production capacity of 0.5 million tons of iron per year. Plants with an annual production of 1.25 million tons are now technologically mature, according to Lang. So why a pilot plant? The pilot plant in Frankfurt is intended to gain further experience with the electric heaters. The actual purpose, however, is to produce sample material on a ton scale. Potential customers can use this to test whether the pig iron is suitable for further process steps, such as melting furnaces.

Economic viability within reach.

The first Circored plant in Trinidad was not able to establish itself on the market and was shut down, even though the plant built by Metso was able to achieve stable operation. The production capacity was too low for economic operation under the conditions at that time.

Whether the CFB technology has a chance in the market depends largely on CO2 pricing and the price of hydrogen. If the CO2 price rises in the coming years as expected and hydrogen costs as much as current estimates predict, the CFB technology would be as expensive as traditional iron production in blast furnaces, according to Metso. Compared to the shaft furnace, it is even said to be significantly cheaper, since the cost for the pelletizing step can be eliminated. This has been demonstrated by calculations from Metso. In addition: “We are very efficient in hydrogen utilization,” says Lang. This can also be an advantage for the new process, as long as the cost and availability of hydrogen remain a bottleneck for carbon-free technologies.