© Natascha Plankermann

“We are experiencing what every energy transition brings: delays,” says Oman’s Energy Minister Salim Al Aufi. He compares the current situation to that of the British Navy, which only managed the switch from coal to oil for powering its ships after a lengthy transition. The minister is not trying to conjure up a heroic myth, but rather to recall what transformations are all about: the right pace, a gradual build-up of infrastructure – and perseverance. For Oman, this currently means acknowledging that certifications and regulations for producing and transporting green hydrogen are complex. They also need to correct illusions about demand. Europe is not honouring the commitments made in joint declarations of intent regarding the offtake of green hydrogen. This has led to a change of course that was palpable at the Green Hydrogen Summit, where EU representatives and Omani decision-makers met in the capital Muscat. The tenor of the meeting: away from mere promises of molecules, towards applications that create value in the country while also stabilising European supply chains.

Export products aligned with CBAM

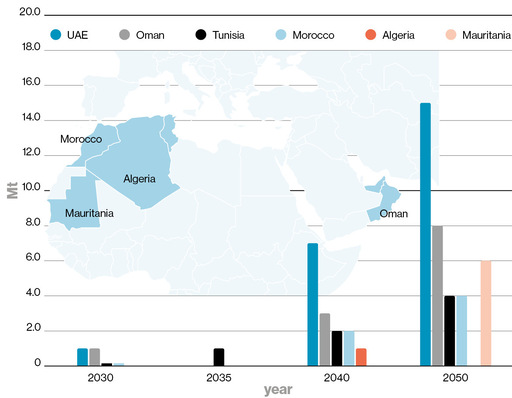

The target remains clear: by 2030, Oman aims to produce one million tonnes of green hydrogen per year, rising to eight million tonnes by 2050. This should enable producers in the country to largely switch to green hydrogen – a plan that fits with the sustainability objectives of the country’s Vision 2040. The green molecules are not to be considered in isolation, but integrated into industrial processes. They are intended to create jobs and deliver export products compatible with the CBAM mechanism (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism). This refers to EU import duties based on carbon footprint. Here lies the connection between Omani industrial policy and European climate regimes: CBAM defines the rules of the game by which production and investments can be aligned.

“Oman does not see the EU’s plans for this carbon border adjustment mechanism as a threat, but as an opportunity to build a competitive green industry and thus create jobs,” says Dawud Ansari, President of the Majan Council think tank in the country and author of the Oman Clean Energy Strategic Outlook.

In this context, potential transport routes to Europe and especially to Germany are becoming increasingly important. “The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) can become a lifeline for Europe’s industry,” says Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, CEO of Hydrogen Europe. This is not a romantic notion of new Silk Roads, but a logic of connectivity. This can apply to crude steel products as well as ammonia deliveries. For ammonia, Chatzimarkakis cites the ACME Group as an example: the Indian energy company is building a plant there that is due to start up at the end of 2026; the first ammonia shipments to Europe are scheduled for early 2027. In the first phase, around 100,000 tonnes of green ammonia per year are planned, potentially rising to almost one million. Initially, ACME intends to use electrolysers from Asian manufacturers, but in the medium term also plans to cooperate with European technology partners such as Thyssenkrupp Nucera.

Those who produce green molecules in Oman and convert them into products that can be used directly in Europe reduce transformation risks on both sides. This explains why projects in Oman’s port city of Duqm are not only targeting ammonia, but also fertilisers and the interface with the steel industry.

© Natascha Plankermann

Intermediate products for the steel industry from Duqm

This is why further industrial plants are being built in Duqm that view hydrogen not as an end in itself, but as a means to an end. Indian steel group Jindal is preparing a plant that is due to start operations in 2027. “It will start production with natural gas and gradually switch to hydrogen,” says Dr Firas Al Abduwani. This path of gradual substitution may seem unspectacular, but it is realistic. It allows operating models to be tested and the hydrogen share to be increased as volumes rise and prices fall. The plan is to supply the European market, particularly Germany, with lower-carbon intermediate products. Interestingly, Jindal Steel International has made a purchase offer for Thyssenkrupp’s steel division (Thyssenkrupp Steel, TKSE). At the time of going to press (mid-January 2026), negotiations were underway regarding a possible gradual takeover.

Singapore-based company Meranti Green Steel is also pursuing the idea of supplying steel intermediate products from Oman – in a form that directly addresses European bottlenecks. “Europe needs such green intermediate products to remain competitive – and politically stable partners like Oman that can deliver,” says Sebastian Langendorf, CEO of Meranti Green Steel and a native of Freiburg in Germany. In Duqm, his company is building a direct reduction plant with a growing share of green hydrogen. The product is HBI, hot briquetted iron, which can be further processed in Europe. The groundwork has been done: gas is allocated by Oman Integrated Gas Company, preliminary investment approval from Oman Invest is in place, as is a banking mandate with KfW IPEX-Bank. The hydrogen partner is Amnah Energy, with a majority stake held by Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners. Construction is scheduled to begin at the end of 2026, with operations due to start in mid-2029. Offtakers of the pig iron include Thyssenkrupp Materials Trading. The transport chain is outlined: via Rotterdam or Antwerp. Duqm reduces, Duisburg refines – CBAM-compatible.

What matters in this phase is not the grand promise of switching everything to hydrogen – rather, benefits and scalability must be properly aligned. This was precisely what experts discussed during a masterclass held by the Fraunhofer Institute for Surface Engineering and Thin Films IST during the summit in Muscat. “So-called sponge iron is the key to low-carbon steel production. Although three direct reduction plants have been commissioned in Germany – in Duisburg, in the Saarland and in Salzgitter – the complete switch to hydrogen remains difficult as long as the costs of green hydrogen do not fall significantly and cheap imports fail to materialise. In this context, Oman can play a central role in Germany’s energy transition and in the market ramp-up of green steel in Europe,” said Florian Scheffler. This is not a rejection of domestic production, but a plea for transitions that work.

Oman

• Population: approx. 4.6 million inhabitants

• Labour market and Vision 2040: The Majan Council think tank estimates that more than 20,000 new jobs can be created through hydrogen and green steel projects.

• Current economic structure: Oil and gas contribute around 37 percent to GDP, with 65 percent of exports and 72 percent of government revenues coming from this sector (2023, GTAI).

• Land potential: 50,000 km² for hydrogen zones.

• Production targets: one million tonnes of green hydrogen per year by 2030, eight million tonnes by 2050.