with the same solar module compared to Central Europe. © Arno Evers, Sunny Houses Samal Island

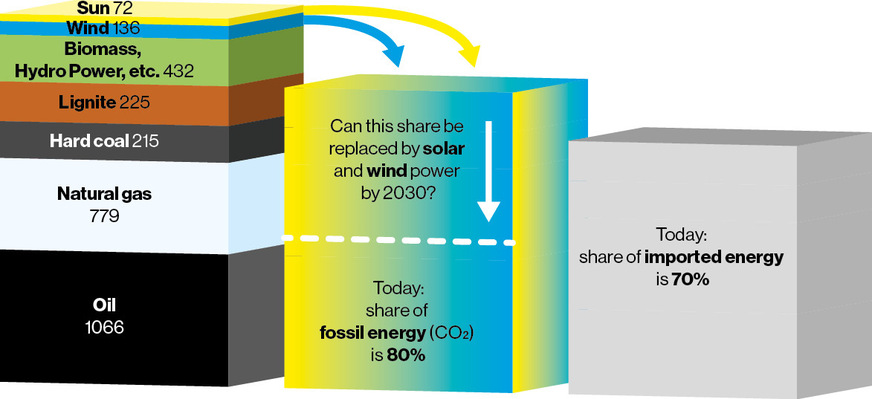

Germany’s transport sector currently consumes around 700 terawatt hours (TWh) of fossil fuels, all of which must be imported, according to the German Environment Agency. The share of domestically generated solar and wind power in Germany’s total primary energy consumption of just under 3,000 TWh is currently only seven percent.

This is significant because only solar and wind energy can provide the scalability required for the energy transition. Further expansion of hydropower and biomass is only possible to a very limited extent. Against this backdrop, it seems highly questionable how green electricity for future e-mobility is to be made available in sufficient quantities, at all times of day and year – and at an affordable price.

Energy demand in the transport sector requires new perspectives That is why I would like to outline the role that hydrogen and its derivatives (e-fuels) could play in the transformation of the transport sector. According to current media coverage, e-fuels are often portrayed as “the devil’s work”: too expensive and inefficient to produce. Only air travel and maritime shipping are accepted as unavoidable exceptions. However, the energy system of the future, including road transport, must be considered as a whole. This is rarely done, nor is there a time-resolved analysis.

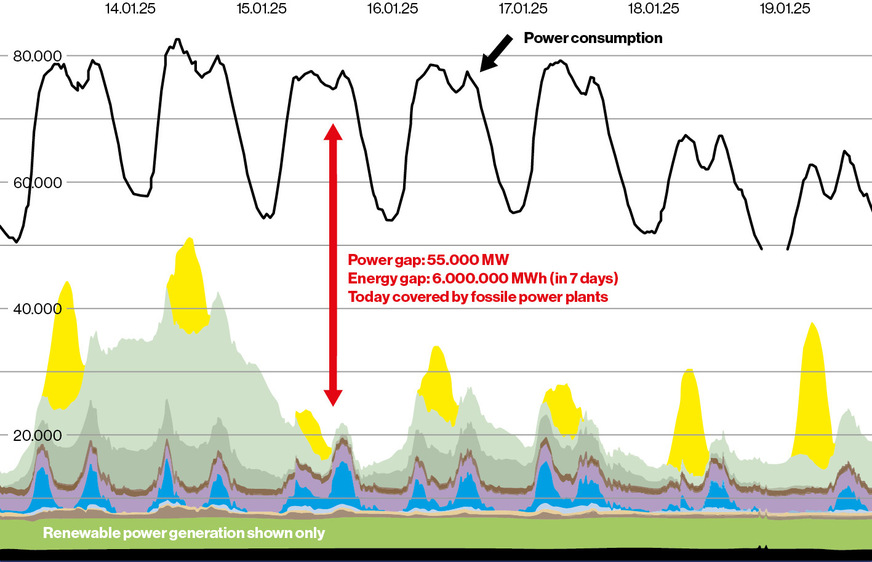

A holistic approach was taken, for example, by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) in 2021: In an energy system based 100 percent on renewable energy, Germany would need around 80 gigawatts (GW) of electrolysers for hydrogen production and 100 GW of flexible hydrogen gas turbines for electricity generation, including for charging electric vehicles. For comparison: today, around 30 GW of flexible natural gas power plants are installed.

However, if green energy were imported in the form of hydrogen or e-fuels from regions with abundant sun and wind, the need for grid expansion could be drastically reduced.

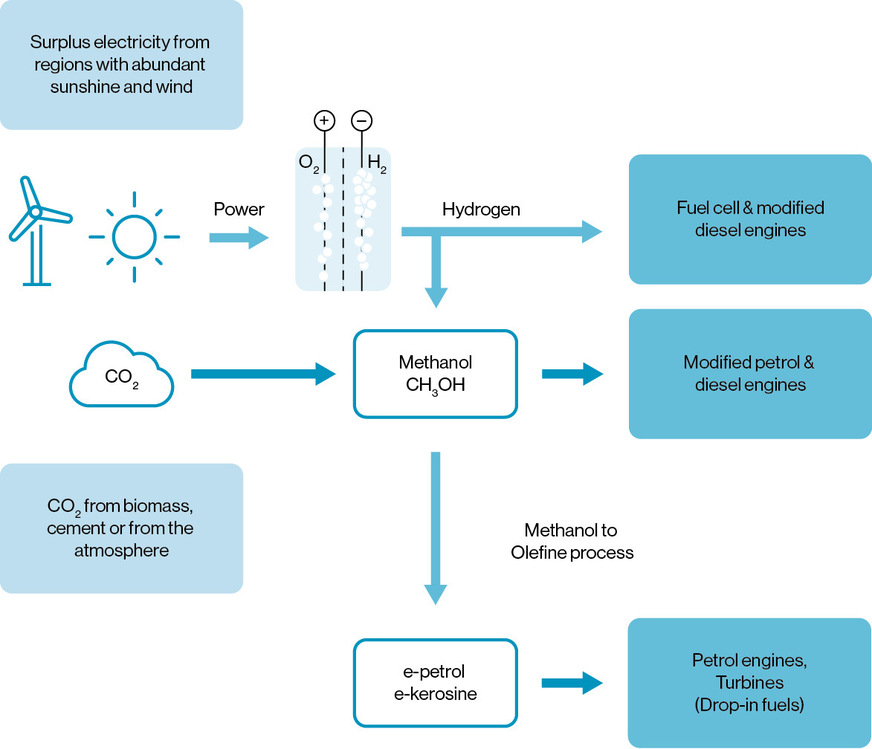

E-fuels from the desert: production and potential Climate-neutral fuels are produced from CO2, water and sunlight. In the future, their production will increasingly take place in the desert regions of the world. In these largely uninhabited areas are hardly any consumers for electricty from solar and wind (Fig. 1). As a result, there is no competition with other applications.

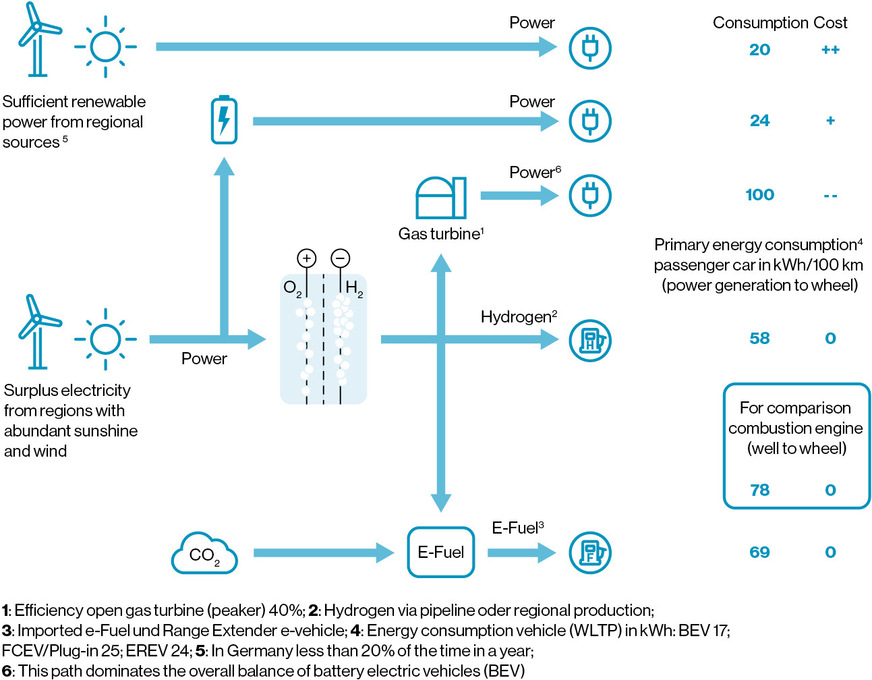

This electricity is used to produce hydrogen via electrolysis, which is then combined with CO2 through catalytic processes to produce methanol (Fig. 2). This methanol can be further processed into e-gasoline or e-kerosene (SAF) and used directly in today’s engines or turbines (drop-in fuels).

Hydrogen and e-methanol can also be used directly in specially adapted engines. The CO2 required for production currently comes mostly from biomass (e.g. from biogas or ethanol production). Industrial CO2 sources, such as from cement production or waste incineration, are also well suited for the production of e-fuels.

The largest potential in terms of volume lies in the absorption of CO2 from the atmosphere (Direct Air Capture, DAC). The second generation of DAC technologies, with significantly reduced energy requirements, is currently under development worldwide, especially in the USA and China. Some companies are also extracting water from the air in addition to carbon dioxide for hydrogen production. In the German-speaking region, for example, Phlair and Obrist are doing this. All other technologies, such as water electrolysis, methanol synthesis or the methanol-to-olefin process for producing e-gasoline or e-kerosene, are industrially established processes.

In recent years, activities related to the production of e-fuels have developed very dynamically. International shipping has become the largest customer for e-methanol. New ships are being equipped with dual-fuel engines. These can initially run on relatively clean marine diesel and then switch to e-methanol as soon as it becomes available or required.

Many production plants for green methanol are currently being built around the world In addition to Chinese companies, Danish firms such as Maersk and European Energy are playing a key role. The Arabian Peninsula is also developing into a hotspot for the production of H2 derivatives such as e-methanol and e-ammonia.

The largest plant, with a capacity of 1.4 million tonnes, is currently being built by Beijing-based company Goldwing in Inner Mongolia. In China, around 50,000 passenger cars are already running on methanol. The use of synthetic fuels in electric vehicles with range extenders (Extended Range Electric Vehicles, EREV) is particularly interesting. In 2024, one million of these efficient vehicles, still powered by fossil fuels, were registered in China. VW plans to launch its first electric SUV with a range extender on the Chinese market this year – aiming to break the 1,000-kilometre range barrier.

This year, Formula 1 is switching to climate-neutral fuels such as e-gasoline. The simultaneously required hybridisation of these powertrains reduces fuel consumption by 25 percent. The e-gasoline is produced by Saudi Aramco. For large-scale production, both Saudi Aramco and some study authors estimate production costs of 80 cents per litre.

Our current energy system is based on oil, coal and natural gas for about 80 percent In Germany as well as globally. These are responsible for the still rising CO2 emissions of around 40 billion tonnes per year (Statista). The infrastructure required for fossil energy – from pipelines to filling stations – has been built and optimised over decades and is still fully operational today.

Oil, coal and natural gas are the most important economic factor worldwide, with revenues of more than six billion dollars per day from crude oil alone. Refining crude oil into everyday fuels triples this revenue.

Since 96 percent of all passenger cars and more than 99 percent of all commercial vehicles on Germany’s roads still run on fossil fuels, a complete transition to climate-neutral energy carriers (electricity, hydrogen, e-fuels) requires a well-thought-out and long-term strategy. Despite their enormous growth in recent years, solar and wind energy currently account for only seven percent of Germany’s primary energy demand.

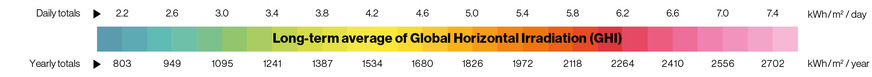

It will remain extremly challenging for them to take on a dominant role in future energy supply. In addition, their volatile generation remains a major challenge. According to the German Weather Service, there are only about 1,800 hours of sunshine per year in Germany, or about 130 sunny days. In the deserts, by contrast, there are 360 sunny days (Fig. 1).

During the remaining 7,000 hours (almost 80 percent of the time), solar power will continue to be unavailable in Germany. Wind is also only available to a limited extent, as high-pressure weather systems can result in little wind power generation for many days or even weeks.

Batteries are only suitable as short-term storage and to buffer temporary high power demand during fast charging. In addition, a regular supply of green electricity is needed to recharge battery storage systems. Most of the time, power plants must meet electricity demand – currently fossil-fuelled, and in the future powered by hydrogen – both for today’s electricity consumption and, increasingly, for charging battery-electric vehicles (Fig. 3).

The currently installed 200 GW of photovoltaic and wind power capacity also lead to temporary electricity surpluses, which, despite very low or even negative prices, find no buyers and must be curtailed. Storing this surplus electricity in the form of hydrogen will be an essential component of the future energy system, as calculated by the German Institute for Economic Research.

What does this mean for the energy supply of tomorrow’s transport sector? The solar and wind energy potential available on Earth exceeds today’s global energy demand many times over. The deserts in the sunbelt and the long, windy coastlines offer the possibility of generating vast amounts of green electricity (Fig. 1). In these mostly uninhabited regions, it can hardly be used unless liquid fuels are produced there. These can then be transported by ship, rail or truck to consumers in the densely populated areas of the world.

E-methanol is one of the most attractive energy carriers for this purpose. It can be used directly in slightly modified engines or further refined into established fuels such as gasoline or kerosene (Fig. 2). If a solar module in sun-rich regions produces two to three times as much electricity as in Germany, but cannot be used locally, then the popular discussion about efficiency becomes irrelevant (Fig. 4). What matters are the costs of producing and transporting the fuel. And don’t forget: the storage issue is already solved for these energy carriers.

The wide range of efficient electric powertrains In public discourse, the term “electric vehicle” is automatically equated with battery-electric powertrains. However, there are many variants of electric drives. Pure battery-electric vehicles (Battery Electric Vehicles, BEV) store the required energy in batteries, which weigh up to 800 kilograms in passenger cars and often more than 5,000 kilograms in trucks and buses.

In fuel cell powertrains (Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles, FCEV), electricity for driving is generated on board from hydrogen. In combination with a much smaller battery that enables regenerative braking, this results in an efficient, emission-free drive that is particularly advantageous for vehicles with high energy consumption and long driving ranges (short refuelling times and lower overall weight). In electric vehicles with a range extender (Extended Range Electric Vehicle, EREV), a small battery (around 20 kWh in passenger cars) is recharged on board by a generator powered by a combustion engine when needed. The engine of the generator operates at a fixed point (speed and power) with high efficiency of more than 40 percent and minimal pollutant emissions.

Refuelling with liquid fuels (e-fuels) works just like in conventional vehicles. In the omnipresent discussion about efficiency, either only the vehicle’s efficiency (from tank to wheel) is considered, or it is assumed that sufficient green electricity is always available for direct charging (Fig. 4, upper path).

However, this is relatively rare – for example, at midday on sunny summer days or during stormy weather.

Intermediate storage in batteries is also only possible to a limited extent. Most of the time, the electricity needed to charge vehicles comes from a thermal power plant with an efficiency of no more than 40 percent. This reduces the overall efficiency from electricity generation to the wheel to below that of combustion engines.

Yet this perspective is almost never considered. The direct use of hydrogen in fuel cell powertrains is even more efficient than a BEV whose electricity comes from a power plant. In the Earth’s sunbelt, solar power is now generated for one cent per kilowatt hour. This can then be used to produce hydrogen very cost-effectively and further processed into e-fuels (Fig. 2).

This is relatively efficient when viewed holistically, and due to the very low electricity prices, it is above all cost-effective. For e-fuels, production costs of eight cents per kWh are expected in large-scale production. That is about twice as much as fossil gasoline costs today.

Thanks to the efficient range extender, consumption would be halved and the cost per kilometre would remain the same. Compared to an electricity price of 80 cents per kilowatt hour at a fast-charging station, this is very inexpensive – even when converted to cost per kilometre. Today, e-fuels are only available in limited quantities, which is why there are no market prices yet. However, these are developing within an already established overall system.

Conclusion From a holistic perspective, e-fuels are an attractive option, especially for efficient range extender electric powertrains. The existing infrastructure for liquid fuels saves investment and enjoys high user acceptance. The extremely costly expansion of charging infrastructure and the power grid, as well as investments in peak-load power plants for demand-driven electricity generation, could then be avoided. Fuel cells, electrolysers and range extenders offer high potential for domestic value creation. They could become a key component of the energy transition, which can only succeed through technological diversity.

(Source of figures: German Environment Agency) © NEONBOLD

the various options of electric vehicles and green fuels. © Werner Tillmetz / NEONBOLD

The load will increase significantly with the further expansion of battery-electric mobility.

© Fraunhofer ISE, Energy-Charts / NEONBOLD

Prof. Dr.

Werner Tillmetz

worked in the automotive and chemical industries for 20 years. At DaimlerBenz and Ballard Power Systems, he led fuel cell development for vehicles until 2002. The electrochemist with a doctorate was a member of numerous committees, including the National Platform for Electric Mobility and the National Organization for Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technology (NOW) of the German Federal Government. To this day, he remains a member of the Science Council of TotalEnergies (Paris) and the Advisory Council of Emerald Technology Ventures (Zurich).